The jurisdictional issue, to take just one area of concern for those interested in what to expect in the way of energy regulation, has been "decided" three different ways since World War II.

The erratic gyrations of the Commission’s attempts to grapple with forces of supply and demand have been matched by judiciary inconsistency. Reliance upon the judicial system to "right" the "wrongs" of the FPC has been largely misplaced. The most immediate avenue to relief is our third option: appealing the decision to the next echelon of government officials, in this case, the courts. This may prove more effective on a cost/benefit basis, but it, too, is future-oriented. While it cannot be neglected, it is not as promising as efforts to influence the decisions of the Commission itself. First, the "wronged" party can go to the legislature and get the law changed. The avenues open to the "victims" in these instances include recourse to all three branches of government. The "injustices" made by law can be unmade by law as well. However, let the "injustice" come at the hands of an agency of the government such as the FPC and we have a whole new ballgame on our hands. One might as well complain about the law of gravity. Such impersonal "injustice" has no remedy. You don’t petition to have the law of supply and demand set aside. If you can’t make a profit in your present trade, you change your occupation. If the market treats you "unfairly," there’s not much you can do about it.

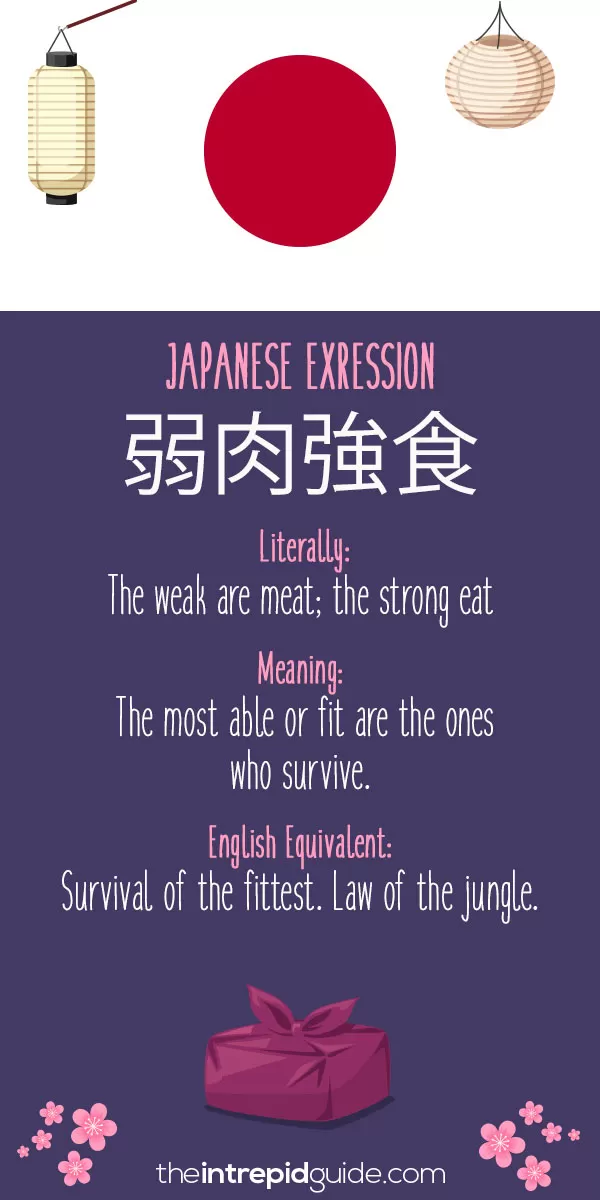

LAW OF THE JUNGLE MEANING FREE

Rather than the certainty promised by the imposition of deliberated policy upon the erstwhile fluctuations of free market "jungle," the resort to regulation has piled confusion on uncertainty with a result that is often incomprehensible. With all this "logic" going for it, it should come as no surprise that the government’s venture into energy regulation has been a disaster. Its rulemaking was restricted only by the proviso that its actions be "just and reasonable." The agency was given a broad grant of authority to insure its capability for a flexible response to changing conditions. Its objective was to control various aspects of the energy industry and thereby promote business prosperity and social justice. Reasoning like this inspired the creation of the Federal Power Commission (FPC) in 1930. With laws to regulate the prices and supplies of a good or service and with the vast information-gathering resources of the government at hand, the number of uncontrolled or unknown variables in the uncertainty equation ought to be reduced. This urge to rationalize the vagaries of the business environment has frequently been manifested in a resort to law as a means of controlling uncertainty. A rational response to such uncertainty is to seek to reduce it through either an improvement of one’s knowledge about, or an increase in one’s control over, the conditions pertaining to a prospective field of endeavor. The more uncertainty there is, the greater the risk for the would-be entrepreneur. The problem of uncertainty is endemic to any business venture.

Semmens is an economist for the Arizona Department of Transportation and is studying for an advanced degree in business administration at Arizona State University.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)